Happy Days: For this Davie legend, it always included a good bird dog

Published 1:04 pm Tuesday, December 5, 2023

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Mark Hager

President, Forks

of the Yadkin and Davie

County History Museum

Before the Green Bay Packers became the first back-to-back Super Bowl champions under the coaching of Vince Lombardi, Davie County made national news.

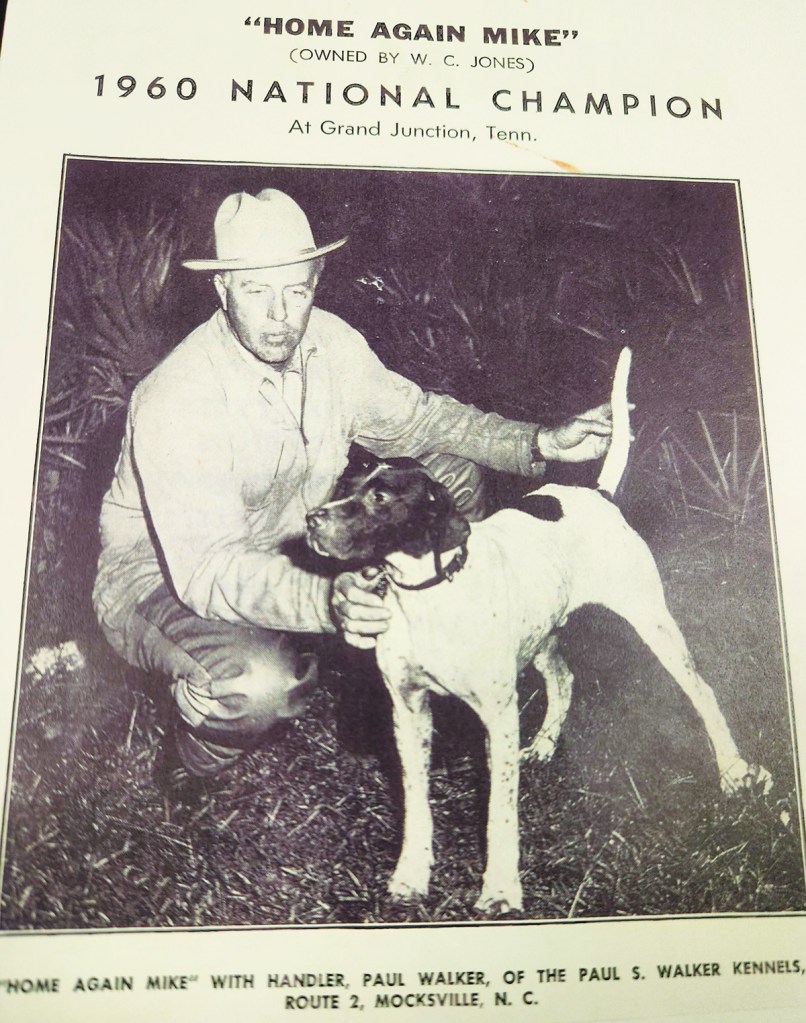

In 1960 and 1961, Davie native Paul Walker won back-to-back national field trial championships through two bird dogs – Home Again Mike and Spacemaster. Both were from the American Field Haberdasher line of English Pointers.

Walker, over a two-decade period, racked up numerous championships. In 1969, he was inducted into the National Field Trial Hall of Fame.

A display in his honor is at the Bird Dog Museum in Grand Junction, Tenn. The museum is operated under the University of Tennessee.

Walker’s legendary status came in a time period when going hunting was understood as: being a responsible hunter, wing shooter, and most importantly, a dog master.

Quail hunting was also a community effort. Even before the Great Depression, farmers welcomed a diet on wild game. Quail was the bird of choice.

Farming practices required a keen eye for habitat. Whether working a mule team or on a tractor, farmers steered to avoid quail nesting sites. Like today, farmers would plant corn, grain, sorghum, and soybeans. However, they would supplement hay needs with lespedeza and sericea.

Other lagoons were added to patches of dense thickets, where plums and blackberries would also thrive. Disking every few years to reestablish better, “quail thicket habitat.”

Some farmers would conduct a controlled burn to foster better wild grass habitat. Rows approximately 15 feet wide around border sections of crop fields were maintained. Farm families understood that the quail brooding season was primarily May and early June. But a late summer, second brood was possible. Fescue was cautioned due to its harvest time during the main brooding season.

After the summer crops were harvested, the fall hunting season ensued.

Each farmer had a pretty good idea where to look for quail. But keeping the covey from flushing before the shotgun was readied was the key.

Then, locating the downed bird and flushing the singles was the difficulty.

A good bird dog was the answer.

Across the region, the dog breed of choice was either an English Pointer or Setter. Popular breeds such as the German Short Hair didn’t arrive in the region until much of quail population had diminished. A properly trained dog would point the covey and hold until the hunters were in position. Most upland bird hunter’s preferred to move in to flush the covey. The dog stayed steady on the point.

Although rare, a few hunters added a command such as, “easy,” which would allow the gun dog to flush. Through years of experience, it became second nature to spot a rooster from the hen, and, with proper coordination using crossfire to bring down multiple birds.

The ultimate shot was taking down two birds with one shot. Afterwards, with the command, “dead bird,” the gun dogs would find and retrieve the downed bird from the cover. The hunting team would then search to find a few single birds from the covey. In an effort to keep the covey healthy, the farmer tried to keep covey numbers at a minimum of 10 birds.

This style of hunting required attention to detail. Knowing the exact location of each hunter and gun dog was second nature. The right shotgun and shot became unique to each hunter. Shooting the bird while, “on the wing,” was difficult to teach. Many found the training learned on a bird hunt as a vital tool for survival on battlefields.

Being on, “point”, and catching the flush in a cross-fire, were just a small part of bird hunting.

Famed Airforce Fighter Ace, Chuck Yeager said most of the successful pilots of WWII first learned the key to bringing down enemy fighters from bird hunting. They were already trained to shoot on the wing. Ammo was expensive and time was precious. Bird hunting wasn’t a sport. It was a continuation of farming.

Davie had more than 200 dairy farms in the 1960s. Each morning before 5, milking started. Afterwards, many had to feed the hogs and chickens.

Somewhere in the middle was crop season preparation. Bird hunting followed crop harvesting and tobacco priming during the fall and winter.

Eugene Hunter can remember a story about a planned hunt with farming neighbor, Odell Boger. Boger had an English Setter named Mack.

Odell and Eugene Hunter’s dad, Francis Reed Hunter, were to meet to bird hunt following the morning chores. Boger’s dog locked on point about a mile from Hunter’s barn. Boger hurried on to meet Hunter but the chores weren’t quite finished.

Boger yelled out, “Let’s go, Mack is on point.”

An hour and half later they returned but the dog was gone. Hunter had an English Setter named “Spot” that found Mack. Apparently, Mack had crept slowly several hundred yards trailing the covey. In bird dog terminology, Spot found Mack and caught the scent of the covey and pointed by “backing Mack.”

Hunter and Boger moved forward and the covey flushed and shotguns blazed and birds came down. Still winded from all the walking Boger and Hunter yelled, “dead bird,” and the dogs went to work retrieving.

They continued hunting until time for evening milking.

Eugene Hunter fondly remembers that time period. He said that as soon as farming was completed, his dad and Spot were in field hunting every day they could. Except Sunday, there was no shooting or hunting. “Never even thought about hunting or shooting on a Sunday. No tractor was even cranked on Sunday.”

It was the Lord’s Day with zero excuse.

Hunter continued: “Back then few places were open on Sunday.”

No hunter wore blaze orange or worried that the other hunter might accidentally discharge a firearm. Discipline and responsibility were ingrained in the hunter and dog, just as Sunday worship meant being in church as a family, and on time.

Bird hunting added excitement to farm life.

WWII Veteran Sheek Bowden smiled when remembering a hunt using his bird dog – Nancy.

WWII Veteran Sheek Bowden smiled when remembering a hunt using his bird dog – Nancy.

“I was at Boone Foster’s farm back around 1960. I was on the right and Boone on the left with a mutual close friend Paul Hodges, in the center. Boone’s dog named, Bill and Nancy locked on point. Hodges, took a step and the sudden noise of 30 quail broke the silence. Most of the birds flushed toward Hodges. Bowden drew his shotgun into his shoulder, and fired twice. He heard the reports from Boone’s shotgun. After a moment of silence, Bowden turned and heard Foster yell, “Junior! Junior! How did you do?” Junior was the common name for Bowden. He replied, “I got two. And you?” Foster replied by pointing towards the ground, “One, two, three!”

All laughed and with the command, “dead bird,” watched as the dogs found and retrieved each bird.

Having the right hunting dog was heaven.

Johnny Marklin remembered many times that his dad Johnson Marklin would join others and hunt up the railroad tracks for coveys. Johnson’s dog, an English Setter named “Ole Joe,” developed quite the reputation, enough so that one local hunter kept coming into their furniture store to ask Johnson to sale him his dog.

Johnny Marklin remembered many times that his dad Johnson Marklin would join others and hunt up the railroad tracks for coveys. Johnson’s dog, an English Setter named “Ole Joe,” developed quite the reputation, enough so that one local hunter kept coming into their furniture store to ask Johnson to sale him his dog.

Johnny remembered his dad stopping the final inquiry with, “I’ve told you. My dog isn’t for sale for any price.”

Years of training and experience with a good bird dog were invaluable. The loss of such a dog was comparable to losing Old Yeller, or for some reading this, an echo from Where the Red Fern Grows.

For Bowden, Nancy was a hunting companion and best friend.

Eugene Hunter most remembered hunting with Sam a lemon and white English Pointer. “He had a good nose. Sometimes pointing a covey 200 feet away, Sam would hold point the entire time. Once the covey flushed and shots were fired, Sam wouldn’t leave point until the command ‘dead bird’ was given.”

The community of bird hunters knew each other well.

Hunter remembered Walker as a serious, good-hearted individual that respected anyone who worked hard and would listen to common-sense.

That was echoed by Jeff Allen, who said most in the area had their own bird dogs, and knew how to train them. If a dog developed an issue, they consulted each other much like a tractor issue discussion of today.

Likewise, finding the right gundog required years of experience. The preferred gun dog breed was second to picking the right pup in a litter. To a well-seasoned trained eye like Walker, a proper pup could be spotted quickly.

Jeff Allen said that Walker would emphasize that getting the right genetics was the key.

Jeff Allen said that Walker would emphasize that getting the right genetics was the key.

The Haberdasher American Field Bred Pointer lineage was the best stock to begin with. Allen learned that, “You look for the pup that flash points a butterfly. Then, flip a wing of a quail using a fishing cane pole, fishing line, and wing to test pointing, but only do this once. Each time the right response was seen, to whistle the sound of a Bob White quail.”

Although several pups in a litter may have positive reactions, it is the pup in the litter with good eye contact and style that became the clear choice.

Being able to “read” a dog became an art form. The hunters with years of experience became a team along with the gun dogs. No whistles were needed. The only commands were: “whoa,” heel or more commonly used then, “come here,” and “dead bird.”

In rare cases you might prefer the dog to flush. In that case, “easy” was the command. Then the dog would slowly creep forward until either “whoa” was yelled or flushing occurred.

“Fetch it up!” was an endearment term rather than command.

Allen said a common phrase from Walker was: “Keep your feet on the ground, meaning God created trainer and dog, likewise, a trainer should place a guiding hand upon the dog. Walker’s most unique command was, ‘Whump’ which meant caution, combining whoa and stop together. Afterwards, he would yell ‘whoa,’ which Walker said means whoa. Stop on the spot and never move. Yelling, ‘come here’ meant return. Walker seldom, if ever, said ‘heel.’ ‘Ho’ meant turn.

“Walker warned to never under any circumstance teach a pointing dog to ‘sit.’ Because under pressure, it would cause the dog to sit until that pressure ended. It would ruin a setter and pointer.

“It all starts at home, Walker would repeat. He would tell others that, ‘If you can’t get the dogs right in the yard, the dog won’t do it in the field’.”

Introducing the dog to the shotgun was a major hurdle. A good trainer carefully introduced the dog to bird and gun. Many a good dog was ruined from an inexperienced trainer firing a 12-gauge shotgun or a 22-caliber rifle too close and too soon. It takes a relationship and respect.

As pups, Allen said it was common to bang the feeding pan around as they were fed, giving positive attention and petting during that time. A few weeks later, and just before feeding time, fire a blank pistol 40 to 50 yards away. Then while feeding, continue the positive attention on each pup.

“A careful eye on a dog’s reaction would determine when a shotgun could be used. There was no exact time for gun use. It took careful attention and experience. The goal was having a broke dog. According to Walker, it is a dog that stops on the verbal command whoa. Then, after the gun shot, waits until the command of ‘dead bird.’ Or if no birds were in the area would return with the command, ‘come here.’

That according to Walker is a broke dog.

Davie County became famous for its gundogs and trainers. The memory of that perfect gundog was there with getting married and the birth of a child.

“Sweet six-teen,” wasn’t a teenager, it was a preferred shot-gun gauge for quail. Likewise, a 4-10 wasn’t the height of a person. Paul Walker, many times carried a 4-10. It was a less expensive round and you could carry more rounds.

With proper training, bringing down a quail didn’t require a large gauge. Paula Spillman, a daughter of Paul Walker, remembered: “Dad had everyone trained to pay attention. There were several occasions that while out with the dogs, he would yell, ‘whump.’ Short for whoa and stop. We all stopped instantly.

“On several occasions it was a snake that caused the attention. None of us, dogs or children would move till Dad took care of it.”

Allen credited much of the success to “Walker’s knack for knowing if the dog was sick or not scenting properly.” Have the young dog point, hold steady, and remain steady when the bird flushes was the dream. A whistle was seldom used. Walker carried a whistle tied around his neck by a shoe string. But the whistle didn’t mean stop, it meant for the dog to hunt or run farther away.

Otherwise, he didn’t use the whistle.

So, what happened to the quail?

Eugene Hunter remembered the birds disappearing in the 1980s. It’s a common question with answers that are variable. Many point to loss of habitat and farming from fence to fence leaving no hedges or thickets. Tractor operators were no longer looking out for nesting areas. Creek banks were being cleared of thickets, wild blackberries and plums. The careful eye of that small family farmer has diminished to that of larger corporate farming.

Just a few family-owned farms remain in Davie County. The last dairy went out a few years ago. Others mentioned, too many domestic cats, coyotes, foxes, and birds of prey are here now.

Jeff Allen, who trained with Paul Walker, heard Walker complain that deer and turkey were causing major issues. Deer would sometimes eat the eggs. The turkey would destroy the nest and kill the hatchlings.

Some have suggested poultry diseases spread into quail populations due to fertilizer from chicken houses.

Rowan County physician Dr. Richard Adams has another idea. He had been studying quail hatch rates since the 1960s. He noticed a sharp decline in hatch rates in the late 1980s. Adams ruled out DDT, as it was outlawed many years earlier. He noted that hatch rates dropped dramatically to less than two percent. But at the same time, domestic quail hatch rates were over 90 percent.

In parts of Texas, Arizona, and Oklahoma, Adams noticed quail were doing well regardless of farming practice and preying animals. It seemed all areas receiving more than 30 inches of rain per year witnessed the loss of quail.

In the same time period, other ground nesting birds such as whippoorwills saw similar reductions. “It didn’t matter how much cover and protection, they just disappeared.” Adams feels something in the air is causing them to become sterile.

The southern “Bob White” populations have been reduced and largely confined to areas of Texas and the Southwest. The whistle of the Bob White in the spring and the sound of a large covey flushing is missed by many.

And with that, the sight and sounds of “pointer’s and setter’s.”

Today, hunting has witnessed drastic changes. It’s no longer a family farm livelihood. For safety measures, hunters are required to wear blaze orange. The hunters a few decades back seldom worried of miss identification. They knew the ground, the hunters, the shotgun, and the dogs. Plus, there were few deer or turkey around before the 1980s. Now they’re here in large numbers.

Deer hunting from a tree stand over a food plot or baited area is the norm. The hunter may not be a neighbor. For personal safety, farmers today wear blaze orange to avoid an “accidental” shootings.

Perhaps the greatest change is hunting on Sunday. I couldn’t imagine asking Dad to miss church to go hunting. Of course, he was a Baptist minister. No hunting or sports was allowed on a Wednesday or Sunday. That included ball practice.

Years ago, I can remember one dairy farmer who heard a hunter mention: “It’s the only day I have off.” The farmer’s reply, “While growing up we worked every day. Our cows, hogs, or chickens didn’t take off for Sunday. But God, and my rear-end, required undivided attention on a certain church pew every Sunday morning and evening. If not, my rearend wouldn’t be able to sit for a week.”

Allen stated that Paul Walker wouldn’t work the dogs or train on Sunday. Back then, even the field trial competitions tried to end on Saturday.

Sadly today, like the quail, church attendance has dropped dramatically. But other weekend entertainment has risen sharply.

The art of bird hunting has faded. But many can still remember, getting that first gun dog, shotgun, and wing shooting. It is an unforgettable memory.

Back then, loyalty wasn’t a brand, it was a lifestyle. “Never trust a man who will trade horses in midstream” was a favored quote from Walker that has stayed with Allen. That applied to many lifelong events to include politics, according to Walker.

In field trials, there was never a participation trophy for bad shooting and improperly trained dogs. But there were no hunting invitations until you learned more responsibility.

Paul Walker, told Allen that “Hard work, preparation, a little bit of luck, and then, God may let you win.”

Above all, Walker would sternly say, “Be a gracious competitor, no matter the outcome.” If you disagree with an outcome that caused you to lose, Walker would say, “That’s the hand you want to shake, judges and handler.”

More telling about Walker’s demeanor is described by Paula and her sister Dixie. They remembered hearing their dad constantly uttering, “Happy Days.”

It didn’t matter the mood or event. Paul Walker had a storied life and became a legend in the upland hunting world.

Walker won many local and regional field trials, plus two back-to-back national championships at the Ames Plantation in Grand Junction, Tenn.

Walker was more than a Hall of Fame champion. Spillman said: “He was the best dad a child could have, and husband to my mom Louise for 68 years.”

Paula said, “Never heard a cross word between them, ever.”

Paul Walker passed away on Jan. 5, 2003. Louise passed away on Aug. 28, 2009.

There is one last point that I would like to end with.

Over this Thanksgiving and Christmas, I hope everyone across Davie County will remember the “Happy Days.”